Dict Lab: A Serious Introduction to C

1 Overview

Most of the C programming you have seen to date pertains to memory representation of objects. In this lab, you will be using C as a full-featured language and implement a dictionary application. This project also introduces some topics that will be covered throughout the session (indicated using “Ch. X” in this text and referring to the chapters of our main textbook).

A sample usage of the dictionary application is as follows; in all the examples,

lines starting with $ denote the commands typed in the shell, and with >

those typed in dict, your program:

$ make make[1]: Entering directory '/home/stu/dictlab/src' gcc -g -Wall -Werror -c -o dict.o dict.c gcc -g -Wall -Werror -c -o main.o main.c gcc dict.o main.o -lmcheck -o dict make[1]: Leaving directory '/home/stu/dictlab/src' $ src/dict > put word:definition > get word definition > put word:changed definition > get word changed definition > del word > get word > CTRL-d goodbye. $

—Note

Typing CTRL-d signals to your program that the input that it is reading (from the “standard input”) has reached the end of file. Your program should end gracefully when reaching the end of the commands.This will rely on a dictionary library that you will implement. The above interaction corresponds to the following code with the library:

dict_t* dict = dict_create (); dict_put ("word", "definition"); printf ("%s\n", dict_get ("word")); dict_put ("word", "changed definition"); printf ("%s\n", dict_get ("word")); dict_del ("word"); if (dict_get ("word") == NULL) printf ("\n"); dict_destroy (dict);

This project is divided into two parts:

- Part 1. You will be implementing a dictionary structure (storing pairs

key/value), and reading the user input to manipulate the structure. The

commands implemented in that stage are

put,get, anddel. It will be important not to leak any memory in these functions. - Part 2. You will add two more commands:

clr, which clears the dictionary, andsiz, which prints the size of the dictionary. Again,clrwill have to make sure not to leak any memory. You will also implement a destructor for your dictionary object.

2 Downloading the assignment

Start by extracting /home/zhuang/public/dictlab-handout.tar.bz2 in your home:

$ cd ~/ $ tar xvf /home/zhuang/public/dictlab-handout.tar.bz2

This will create a dictlab directory and unpack a number of files into the directory. /You

should only modify the files src/main.c and src/dict.c, and these are the

only files that are submitted./ The test folder contains the different tests

and grading examples for your program. Use the make command to compile your

code and the command make test to run the test driver. This would run all the

tests for all three parts, which is not really useful while working; see Section

6.2 for more finely grained testing options.

3 Structure of the project

There are two distinct aspects to that project, that are made clear by the fact

that you will code in two different files in the src/ folder: main.c and

dict.c. The file dict.c will implement a dictionary library, which

creates and manages a data structure for key/value pairs. The file main.c

will be in charge of providing the user interface: read the commands, execute

them using the dictionary library, and print the results to the user.

The two parts are independent in the sense that the library does not depend on

the user interface (it could be reused in other projects) and the user

interface could use any implementation of the library interface (spelled out in

dict.h which you are not allowed to modify). The file main.c is in no way

allowed to access the dictionary structure through any means other than the

library functions that you will implement.

The dictionary library will have to define a dictionary type dict_t and

implement the following functions (listed in dict.h and to be implemented in

dict.c):

// Create a dictionary. dict_t* dict_create (); // Free a dictionary. void dict_destroy (dict_t* dic); // Put an element in a dictionary. key is case sensitive, val is a string. If // the key already exists, its value is updated. If val is NULL, the pair is // deleted. void dict_put (dict_t* dic, const char* key, const char* val); // Return the value associated with key, or NULL if none. char* dict_get (const dict_t* dic, const char* key); // Delete the pair associated with key. void dict_del (dict_t* dic, const char* key); // Return the size of the dict. size_t dict_size (const dict_t* dic); // Delete all elements in a dictionary. void dict_clear (dict_t* dic); // Apply fun to each pair key/val; arg is an extra argument passed to fun. void dict_apply (const dict_t* dic, const dict_apply_fun_t fun, void* arg);

The user interface, implement in main.c, starts with an empty dictionary and

will have to be able to interpret the following commands:

put KEY:VALUE: assignVALUEtoKEYin the dictionary.get KEY: return the value associated withKEY.del KEY: delete the pair associated withKEY.siz: print the size of the dictionary.clr: empty the dictionary.

4 Part 1: get, put, del

4.1 Dictionary library (dict.c)

In Part 1, you will have to implement the bulk of the dictionary library in

dict.c.

4.1.1 Dictionary structure

You will start by giving a definition for your main structure

struct dict. (You cannot change the name of this type, it is however aliased

(typedef’d) in dict.h as dict_t to avoid having to type struct each

time.)

For instance, you may want to have a dictionary implemented as a linked list; in that case, you can store the head of that list and its length in your structure:

struct dict { struct dict_list* head; size_t size; };

The first field is a pointer (*) to the head of the list, that is, its

memory address. The struct dict_list itself contains the key, the value, and

the address of the next element in the list:

struct dict_list { char* key; char* val; struct dict_list* next; };

The end of the list is signaled by having next be NULL.

—Note

The definition ofstruct dict_list should appear before struct dict since the latter

uses the former. C compilers read files from top to bottom and it is

sometimes forcing illogical presentation of the code—but there is a way out:

forward declarations. For example, let’s assume that you want your main

function to be at the top of your main.c file (it’s a matter of taste after

all). However, your main function uses say a function execute_command

which is also defined in main.c. To avoid having the code of

execute_command before main, you can simply indicate to the compiler that

there will be such a code later on. You do this by just repeating the

function’s type, with no code, before main:

// Forward declaration. void execute_command (const char* cmd); int main (int argc, char** argv) { ... } void execute_command (const char* cmd) { // Actual code }

This is in fact what happens with C header files: they only contain the declarations of functions, but the code appears in other files. These forward declarations are further resolved during linking (Ch. 7).

4.1.2 dict_create

Equipped with these structures, start by implementing:

dict_t* dict_create ();

This function should allocate a new structure of type dict_t (aka struct

dict), initialize its members, and return the newly allocated structure. To do

so, you will call malloc to allocate a sufficient amount of memory:

dict_t* ret = malloc (sizeof (dict_t));

Then, you should initialize the fields of ret. Since ret is a pointer, to

access the object it points to, you should use *ret; hence the size field is

accessed using (*ret).size. C has a shorthand notation for this very common

construct:

ret->size = 0;

Now make sure to initialize head (since its value is garbage as it was just

allocated) and you are done and can return ret.

You will be implementing dict_destroy in Part 2; this is the function that

will be in charge of freeing the memory that was just allocated: in C, memory

that is malloc’d is never automatically freed. Memory allocation is the

topic of Ch. 9.

4.1.3 dict_get

Next, you will implement:

char* dict_get (const dict_t* dict, const char* key);

This function goes through the list given by dict. If you use the above

structure, this means starting at el = dict->head and checking each time

whether the key at el is key; if it is not, we set el = el->next, until

either key is found, or we reach el == NULL.

To compare key with el->key, we need to compare one by one each character in

key with those in el->key. Remember that strings in C are just pointers

(memory addresses) to the first character in the string, so comparing el->key

== key will not do what you want. So how do you even get the length of a

string s? You would start at memory location s and advance as long as the

byte at s (i.e. *s) is not the end-of-string marker (\0, the NULL

character). This can get a bit messy, so luckily, you are allowed to use the

string comparison function strcmp(3) provided by the standard library:

strcmp (s1, s2): returns 0 iffs1ands2are the same strings. Hence inif (strcmp (s1, s2))..., the condition holds if the strings are different—be careful.

If key is found, return the corresponding value; otherwise, return NULL.

—Note

You will remark that the type of the argumentdict is not simply dict_t* but

const dict_t*. This is used to indicate to the compiler that the function

dict_get guarantees that it won’t modify the contents of dict (that is,

*dict). These indications are crucial to providing clear contracts to the

user, helping the compiler make correct assumptions, and avoiding modifying

objects you did not intend to modify.

4.1.4 dict_put

It is now time for:

void dict_put (dict_t* dict, const char* key, const char* val);

This function stores the pair key / val in the dictionary dict, possibly

erasing the previous value associated with key.

It should make private copies of key and val as required. This means that

the function cannot use, for instance, my_element->val = val. To make a copy

of a string s, one could:

- allocate

strlen(s) + 1bytes usingmalloc(3)(strlen(3)returns the length of a string, not counting the end-of-string marker) - go through the

strlen(s) + 1bytes ofsand copy each byte, using either a loop or the functionmemcpy(3)

Again, the standard library provides a function for this:

strdup(3)—remember that since its return value was malloc’d, it

needs to be free’d.

The function works as follows:

- If

keyis found indict, then the associated value should be freed and replaced by a copy ofval. - If

keyis not found indict, then a new element is added to the list; that element’s key is a copy ofkeyand its value is a copy ofval.

4.1.5 dict_del

Finally, you should implement:

void dict_del (dict_t* dict, const char* key);

This function goes through dict searching for key, if it finds it, it should

delete the corresponding key/value pair. The memory allocated for the element

and its key/value pair should be free’d. If the key does not exist, this

function does nothing.

4.2 User interface (main.c)

The main function will contain the main loop of your program and should behave

like this:

- Create an empty dictionary

- Print

"> "on the standard output (this is important). - Read the command from the user; the first three characters are the command

name, then a space, then the arguments, and a newline character

\n. - If the command is unknown, exit.

- If end-of-file was read (EOF), destroy the dictionary, print "goodbye." followed by a newline and exit.

- Otherwise, execute the corresponding command and go back to 2.

To read from the standard input, you will be using the stream reading functions

from the standard library, with stream being stdin, a variable defined in

<stdio.h>:

int fgetc(FILE* stream): read one character of the given stream. This returns the constantEOFon end of file.char* fgets (char* s, int size, FILE* stream): read in at most one less thansizechars fromstreamand stores them into the buffer pointed to bys. Reading stops after an EOF or a newline. If a newline is read, it is stored into the buffer. A terminating null byte (\0) is stored after the last character.

The function fgets is a bit tricky to work with when you want to read a whole

line. Indeed, if the line is very long, fgets needs to be called multiple

times. A video aside for this lab walks you through implementing a robust

“readline” function.

To write to the standard output, you will be using printf(3).

—Note

All thesef* functions are buffered: since actually reading and writing to

a file is very costly (it requires a system call, Ch. 8), these actions are

done in temporary buffers in memory, and system calls are made only when needed

(buffer full when writing, buffer empty when reading). We will see more about

buffering in Ch. 10. Let us simply note the two following consequences of

using buffered input/output:

- Calling

fgetcmultiple times to get a full line is nearly as efficient as callingfgets. - Writing is done to a temporary buffer and is actually sent (flushed) to the

stream (e.g.,

stdout) when the buffer is full orfflush (stream)is called. You need not worry about this for this lab, since you will be interacting with the program on a terminal, where flushing is automatically done after each call toprintf(3). To emulate this, the driver calls your program withstdbuf(1)to disable buffering. If it weren’t doing this, the driver would be stuck trying to read data thatdictwould have stored in a buffer, but not flushed.

4.2.1 Commands

The three commands to be implemented in this part are:

get KEY: print the value associated withKEYfollowed by a newline\n. If no such value exists, a blank line is printed.put KEY:VALUE: store the pairKEY/VALUE. Note that bothKEYandVALUEcan be arbitrary strings, with the only guarantee being thatKEYdoes not contain a colon. Additionally, these strings don’t contain a newline\n. Nothing is printed in return.del KEY: delete the pair associated withKEY, if it exists. Nothing is printed in return, even if the key does not exist in the dictionary.

5 Part 2: clr, siz

5.1 Dictionary library (dict.c)

5.1.1 dict_clear

You will implement the function:

void dict_clear (dict_t* dict);

This function clears the dictionary dict, destroying each pair key/value, but

does not destroy dict itself (remember that dict was allocated using

dict_create, so it will need to be freed at some point, but this is not this

function’s job.)

In practice, if you use a linked-list implementation, you will start at

dict->head and free each key and val, then free the dict_list

object itself, before going to the next element. It is strongly recommended

that you do not implement this recursively. By saving the next pointer

before freeing the element, you will make sure that you are not trying to access

a field in a destroyed variable.

—Note

When youfree a memory location, the memory is usually not overwritten, but

simply put in a pool of “available” memory. This means that if you try to

access that memory, your data is usually still there. This may hide bugs and

create very random crashes. To avoid this, your program is compiled with

-lmcheck; as a result, a different implementation of malloc and free is

used which makes sure that your program crashes if you try to access a memory

location that has been freed. We will see more of this in Ch. 9.

5.1.2 dict_destroy

This is now the function that frees (destroys) a dictionary:

void dict_destroy (dict_t* dict);

This operates just as dict_clear, but in addition should free the memory that

was allocated during dict_create. After a call to this function, if any other

library function receives the pointer dict, the behavior is undefined (most

likely, it will crash).

—Note

You may be tempted to setdict to NULL at the end of that function, hoping

that this will make it clear to the user that the pointer is now invalid.

However, changing the value of dict in dict_destroy will have no impact on

the value of dict outside of the function. This is because in C, arguments

are always passed by value, that is, the value of the argument is copied when

making the call. This is also why we never pass a struct as argument to a

function: we want to avoid copying the whole structure when making the call.

Additionally, passing a pointer to a struct allows the called function to

modify the fields in a way that the caller will see.

5.1.3 dict_size

This simple function returns the current size of the dictionary:

size_t dict_size (const dict_t* dict);

—Note

The typesize_t is a standard alias for unsigned long, that is, a 64-bit

unsigned integer type. It is defined in the header file stddef.h, which is

included by most standard headers (e.g., unistd.h, stdio.h, …).

5.2 User interface (main.c)

Two new commands should now be made available:

clr: clear the dictionary. Nothing is printed in return.siz: print the current size of the dictionary.

The only difficulty here is that your previous commands had argument(s), while these two have none. Here is an example run:

$ src/dict > put a:b > siz 1 > put a:c > siz 1 > get a c > clr > siz 0 > get a >

Also, now that dict_destroy is available, your program is expected to call it

when finishing treating the input. Consequently, your program should have no

memory leaks.

6 Evaluation

6.1 Points

The dictlab is graded as follows:

- Basic: 210 points, basic test on Part 1 and 2

- Part 1: 60 points, comprehensive test on Part 1

- Part 2: 30 points, comprehensive test on Part 2, 6 of which are for lack of memory leaks

6.2 Driver

This project is evaluated by a test driver. You can run the full driver by

typing, at the root of your project, i.e. dictlab:

$ make test

For each test, the driver prints what is the command executed. For instance, the command:

$ ../src/dict < ./traces/short-P1-01.txt

runs ../src/dict and executes the commands found in

./traces/short-P1-01.txt.

The result, for each test, is readily printed; in bracket, there’s a shorthand notation for the result:

OK: Test passedKO: Test failed, yourdictprinted something unexpectedTO: Time out, yourdicttook too long to answer, it’s usually caused by an infinite loop. See Section GDB for more on how to debug time outs.MM: Memory problem, yourdictmade an illegal memory access (or other similar errors, as printed.) Valgrind will list the line in which the problem occurred. See Section Valgrind for more on Valgrind on how to debug memory problems.

—Note

The driver is executed from thetest directory, hence to access the dict

executable, it needs to call it as ../src/dict, which means “go to the parent

directory, then to the src directory, then find dict.”

—Note

The driver uses commands found in a text file. To provide them todict, it

replaces the standard input of dict with the file. This is done, in a shell,

using the redirection <. For instance, the program cat(1) reads

files passed as argument and

prints them as-is. If no argument is provided, cat will read from its

standard input:

$ cat hello ← typed by user hello ← printed by cat CTRL-d $

Hence using cat /tmp/test.txt and cat < /tmp/test.txt do exactly the same

thing: they print /tmp/test.txt. In the first case, cat reads the file

provided as argument, in the second, the shell redirects the contents of

/tmp/test.txt to the standard input of cat. We will see how the shell does

this in Ch. 10. Can you guess what cat /dev/stdin < /tmp/test.txt do?

7 Tools

7.1 GDB

You should be fairly familiar with GDB at this point, but here are a few tips.

Run your program with arguments or with a redirection:

(gdb) r arg1 arg2 < file1

This will run your program with arguments

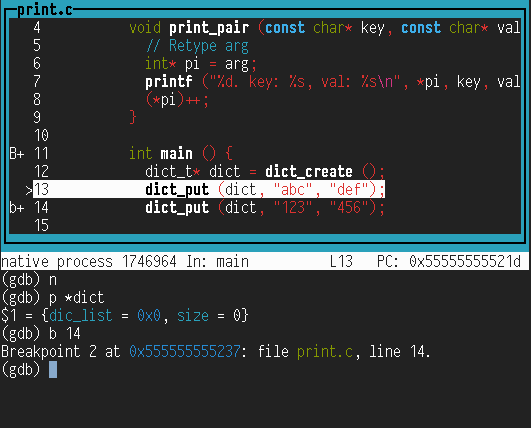

arg1 arg2and replace the standard input withfile1. To silence the output of your program, you can add> /dev/nullto that command line.Print variables:

(gdb) p *dict $1 = {head = 0x0, size = 0} (gdb) p dict->size $2 = 0The command

pcan print a lot of objects. It is not limited to variables, as you can call functions with arguments:(gdb) p (int) strlen ("lorem") $3 = 5Put/delete/list breakpoints:

(gdb) b main Breakpoint 1 at 0x1150: file main.c, line 63. (gdb) b main.c:77 Breakpoint 2 at 0x1276: file main.c, line 77. (gdb) d 2 (gdb) info b Num Type Disp Enb Address What 1 breakpoint keep y 0x0000000000001150 in main at main.c:63

Continue from a break point:

Breakpoint 1, main (argc=1, argv=0x7fffffffe078) at main.c:63 63 int main (int argc, char** argv) { (gdb) cWith a numeric argument,

cwill skip the next crossings:(gdb) c 3 Will ignore next 2 crossings of breakpoint 1. Continuing.

The command

untilcan be used to continue until a certain line is reached:(gdb) until main.c:72 main (argc=<optimized out>, argv=<optimized out>) at main.c:72

Stepping into/over, finishing a call:

Breakpoint 5, cmd_del (dict=0x55555555a2f0) at main.c:151 151 dict_del (dict, del_arg); (gdb) s dict_del (dic=0x55555555a2f0, key=0x55555555abc0 "x") at dict.c:275

The command

ssteps into a call.Breakpoint 5, cmd_del (dict=0x55555555a2f0) at main.c:151 151 dict_del (dict, del_arg); (gdb) n 152 free (del_arg);

The command

nsteps over calls. When in a function, the commandfinishcompletes the call, hencesfollowed byfinishis the same asn:Breakpoint 5, cmd_del (dict=0x55555555a2f0) at main.c:151 151 dict_del (dict, del_arg); (gdb) s dict_del (dic=0x55555555a2f0, key=0x55555555abc0 "x") at dict.c:275 275 dict_list_t* el = dict_find_elt (dic, key); (gdb) finish Run till exit from #0 dict_del (dic=0x55555555a2f0, key=0x55555555abc0 "x") at dict.c:275 cmd_del (dict=0x55555555a2f0) at main.c:152 152 free (del_arg);

Looking up and down the call stack:

Breakpoint 5, cmd_del (dict=0x55555555a2f0) at main.c:151 151 dict_del (dict, del_arg); (gdb) s dict_del (dic=0x55555555a2f0, key=0x55555555abc0 "x") at dict.c:275 275 dict_list_t* el = dict_find_elt (dic, key); (gdb) bt #0 dict_del (dic=0x55555555a2f0, key=0x55555555abc0 "x") at dict.c:275 #1 0x00005555555559ab in cmd_del (dict=0x55555555a2f0) at main.c:151 #2 0x0000555555555276 in main (argc=<optimized out>, argv=<optimized out>) at main.c:75 (gdb) up #1 0x00005555555559ab in cmd_del (dict=0x55555555a2f0) at main.c:151 151 dict_del (dict, del_arg); (gdb) down #0 dict_del (dic=0x55555555a2f0, key=0x55555555abc0 "x") at dict.c:275 275 dict_list_t* el = dict_find_elt (dic, key);

In this example, we first step into

dict_del, then print the call stack (btstanding for backtrace). Then we move around the call stack usingupanddown; note that this does not change the current instruction, we are just visiting the call stack.History: Use the Up and Down arrow keys to navigate your history, which is persistent across sessions. To search for something you typed recently, hit CTRL-r:

(gdb) r very long command line carefully crafted < input > output ... (gdb) CTRL-r and typing "r v" (reverse-i-search)`r v': r very long command line carefully crafted < input > output

Graphical interface. That’s right, GDB has a very nice user interface:

To access the interface, type

tui enable(tuistands for Text User Interface). In that mode, the arrow keys move up and down the code, while CTRL-p and CTRL-n behave like your usual history keys. If you print things in your program, this will garble the output of GDB; you can either refresh the GDB window by typing CTRL-l, or run your program with> /dev/null(see first GDB tip).

You can run your code with a long trace, but in GDB. You can then stop GDB using CTRL-c, and see where it is stuck:

$ make test * PART 1 [TO] ../src/dict < /home/zhuang/.../traces/grading-P1-01.txt CTRL-c $ gdb src/dict (gdb) r < /home/zhuang/.../traces/grading-P1-01.txt > /dev/null CTRL-c (gdb) bt

7.2 Valgrind

valgrind(1) is a complete suite of tools for debugging and profiling

programs. Out of the box, valgrind checks whether a given program makes

illegal memory accesses or leaks memory. To use it like that, we simply prefix

the command line with valgrind. Consider the following program:

int main () { char *s = malloc (10); s[10] = 'a'; }

This program has two problems: It doesn’t free the allocated memory and it does

an illegal memory access (s[10] being out of bound). Valgrind clearly reports

this:

$ gcc -g leak.c -o leak $ valgrind ./leak ==1669915== Memcheck, a memory error detector ==1669915== Copyright (C) 2002-2017, and GNU GPL'd, by Julian Seward et al. ==1669915== Using Valgrind-3.16.1 and LibVEX; rerun with -h for copyright info ==1669915== Command: ./leak ==1669915== ==1669915== Invalid write of size 1 ==1669915== at 0x109157: main (leak.c:3) ==1669915== Address 0x4a5b04a is 0 bytes after a block of size 10 alloc'd ==1669915== at 0x483A77F: malloc (vg_replace_malloc.c:307) ==1669915== by 0x10914A: main (leak.c:2) ==1669915== ==1669915== ==1669915== HEAP SUMMARY: ==1669915== in use at exit: 10 bytes in 1 blocks ==1669915== total heap usage: 1 allocs, 0 frees, 10 bytes allocated ==1669915== ==1669915== LEAK SUMMARY: ==1669915== definitely lost: 10 bytes in 1 blocks ==1669915== indirectly lost: 0 bytes in 0 blocks ==1669915== possibly lost: 0 bytes in 0 blocks ==1669915== still reachable: 0 bytes in 0 blocks ==1669915== suppressed: 0 bytes in 0 blocks ==1669915== Rerun with --leak-check=full to see details of leaked memory ==1669915== ==1669915== For lists of detected and suppressed errors, rerun with: -s ==1669915== ERROR SUMMARY: 1 errors from 1 contexts (suppressed: 0 from 0)

The test driver will use Valgrind to check that you correctly free your memory.

Valgrind can help you track very precisely where the leaked memory was

allocated, using the option --leak-check=full:

$ valgrind --leak-check=full ./leak ... ==67107== 10 bytes in 1 blocks are definitely lost in loss record 1 of 1 ==67107== at 0x483A77F: malloc (vg_replace_malloc.c:307) ==67107== by 0x10914A: main (leak.c:2) ...

As the driver uses Valgrind to run your program, it will uncover wrong memory

accesses that could well not appear when you run your program yourself—out of

sheer (un)luck! If a test fails with the MM code, a Valgrind trace is printed

showing where you made an illegal memory access. To reproduce this, you could

run Valgrind yourself:

$ make test

...

[MM] ../src/dict < /home/zhuang/dictlab-grading/traces/grading-P1-01.txt

==2394868== Invalid read of size 1

...

$ cd test

$ valgrind ../src/dict < /home/zhuang/dictlab-grading/traces/grading-P1-01.txt > /dev/null

==2399692== Memcheck, a memory error detector

==2399692== Copyright (C) 2002-2017, and GNU GPL'd, by Julian Seward et al.

==2399692== Using Valgrind-3.16.1 and LibVEX; rerun with -h for copyright info

==2399692== Command: ../src/dict

==2399692==

==2399692== Invalid read of size 1

==2399692== at 0x4F95B50: __strcmp_avx2 (in /usr/lib64/libc-2.28.so)

==2399692== by 0x400BE7: dict_get (dict.c:56)

==2399692== by 0x400DD5: main (main.c:18)

==2399692== Address 0x5237e00 is 0 bytes inside a block of size 506 free'd

==2399692== at 0x4C31F94: free (vg_replace_malloc.c:538)

==2399692== by 0x400C5F: dict_del (dict.c:69)

==2399692== by 0x400EDD: main (main.c:39)

==2399692== Block was alloc'd at

==2399692== at 0x4C30DE7: malloc (vg_replace_malloc.c:307)

==2399692== by 0x4EC61AD: strdup (in /usr/lib64/libc-2.28.so)

==2399692== by 0x400B63: dict_put (dict.c:44)

==2399692== by 0x400E9F: main (main.c:33)